Social Justice & Conflict Transformation: An Interest-Based Approach

This module was created by Ken Cloke and Duncan Autrey. It will provide concepts and tools to enable users to:

- To apply conflict resolution theory, tools and practices to support their work for social justice and political change.

- Learn about the differences between power-based, rights-based and interest-based approaches to conflict.

- Understand the intrinsic relationship between conflict and social change.

- Consider the concepts behind transformative justice as an intersection of conflict transformation and social justice.

- Develop guiding principles for supporting just and sustainable movements.

- Explore answers to some of the sticky questions arising from tensions between conflict resolution and social justice.

This module will address the following Core Competencies

- Establish conditions for learning and transformation

- Evaluate & improve relationships and systems

- Support healing and restoration during and after conflict

- Restore hope, trust and a sense of belonging

Many of the values that motivate social justice movements are also foundational to conflict resolution. Conflict resolution methodology has the potential to facilitate and support progressive social change; however, social justice activists and conflict resolution practitioners may also encounter tension between different theories and strategies. The heart of this dilemma was expressed in Martin Luther King Jr.’s chant outside a prison holding Vietnam War protesters in 1967: “There can be no justice without peace and there can be no peace without justice.” Real social transformation must include both justice and peace and sustainable solutions must address the needs and interests of everyone involved.

Making justice an integral part of conflict resolution and the search for peaceful solutions means not merely settling conflicts, but preventing, resolving, transforming and transcending them by turning them into levers of dialogue and learning, catalysts of community and collaboration, and commitments to preventative social, economic and political change. When we fail to do this, we make justice secondary to peace, undermine both, guarantee the continuation of chronic conflicts, and lay the groundwork for more to come.

When conflict resolution fully embraces the principles of equality, inclusion, and interest-based approaches to conflict resolution, such as mediation, dialogue, and collaborative negotiation, it can become revolutionary and transformative. Social justice activists can draw on the revolutionary potential within conflict resolution approaches to help them achieve their aims where other methods, including power- and rights-based struggles, have reached an impasse or are at risk of destroying relationships.

From Power and Rights to Interests[1]

Political conflicts can only support justice and serve as engines of constructive social, economic and political development if the means and methods by which they are resolved promote equitable, collaborative and democratic ends. Yet the principal means we have used to resolve political conflicts for thousands of years have relied on the exercise of power over and against others, triggering cascades of war, genocide, rape, terror, domination and suppression directed primarily at those seeking change, self-determination and justice.

What we now require are interest-based methods for resolving social, economic and political conflicts that integrate peace with justice and undermine the temptation to resort to aggression and war. These include, but are not limited to, informal problem-solving, prejudice reduction, collaborative negotiation, team and community building, consensus decision-making, public dialogue and mediation.

The problem with most efforts to address injustice is that they use power- or rights-based approaches that result in deeper polarizations, resistance, and win/lose outcomes that simply trade one form of injustice for another. One side then becomes frightened of going too far, tired of fighting, or willing to tolerate continuing injustices in order to settle the conflict rather than prevent, resolve, transform or transcend it.

Approaching injustice from an interest-based perspective means listening to the deeper truths that gave rise to it, extending compassion even to those who have committed evil acts and injustices, and seeking not merely to replace one evil or injustice with another, but to reduce their attractiveness by designing outcomes, processes, and relationships that encourage former enemies to work collaboratively to satisfy their mutual interests.

Injustice can therefore be redefined as a byproduct of reliance on power- and rights-based methods and failures to implement more advanced interest-based solutions. All political systems generate chronic conflicts that reveal their internal weaknesses, external pressures and demands for evolutionary change. Power- and rights-based systems are win/lose and therefore adversarial, unstable and drawn to avoid, deny, resist and defend themselves against change. As a result, they suppress conflicts or treat them as purely interpersonal, leaving insiders less informed and able to adapt, and outsiders feeling they have been treated unjustly and contemplating unjust actions in response.

As pressure to change increases, power- and rights-based systems must either learn to adapt or turn reactionary and take a punitive, retaliatory attitude toward those seeking to increase social justice, thereby delaying their own evolution. Only interest-based approaches are able to transparently seek out systemic weaknesses, proactively evolve, transform conflicts into sources of learning and change, and celebrate the dissenters who brought injustice to their attention.

Conflict and Social Change

Conflict is the principal means by which significant social, economic and political changes have taken place throughout history. Wars and revolutions can therefore be understood as efforts to resolve deep-seated and chronic social, economic and political conflicts for which no other means of resolution were recognized or accepted by either or both sides, blocking interest-based evolutionary change and systemic improvements.

When conflicts and pressure to change accumulate, even trivial interpersonal disputes can stimulate far-reaching systemic transformations. In any fragile system, be it familial, organizational, social, economic, political or ecological, genuinely resolving conflicts at their chronic and systemic source can be a dangerous, even revolutionary, activity because it encourages people to redress social injustices, collaborate on solutions and evolve in democratic ways that could fundamentally transform the system itself. Indeed, every collaborative, democratic, interest-based effort to resolve systemic conflicts is a small but significant transformation in the dysfunctional system that gave rise to them.

Collaborative interest-based processes thus broaden and “socialize” chronic conflicts, allowing us to address their systemic sources through dialogue, systemic analysis and design, collaborative negotiation, mediation and systemwide, strategic improvements, rather than by political intrigue and infighting. Responsibility for resolving conflicts can then be extended beyond a small circle of antagonists to include allies, partners, bystanders and others whose participation make complete solutions possible, including our opponents.

Yet we can go still further and develop preventative, strategic, scale-free approaches to conflict resolution that, for example, use storytelling techniques to promote understanding between hostile social groups, dialogue techniques to stimulate acknowledgment between representatives of opposing points of view, public policy and environmental mediation techniques to locate complex solutions to intractable international problems, prejudice reduction and bias awareness techniques to increase cross-cultural recognition and empowerment, heart-based techniques to promote reconciliation and redemption.

Whether our conflicts are intensely personal and between private individuals, or intensely political and between nations and factions, three critical capacities are required to spark ongoing improvement and transformational change:

- Personal capacity for mindfulness, integrity, learning and heartfelt communication

- Interpersonal capacity for egalitarian relationships, collaborative negotiation and democratic dialogue

- Systemic capacity for designing preventative, strategic approaches to social, economic, political and ecological disputes and encouraging positive attitudes toward diversity, critique and change

Development in these areas will significantly improve our ability to resolve international disputes before they become needlessly destructive. It will also require us to creatively combine conflict resolution systems design with strategic planning and team building techniques; mediation with heart-based or spiritual practices; community organizing with public dialogue and prejudice reduction; and collaborative negotiation with relationship building, emotional intelligence and community empowerment.

It will further require us to recognize that interest-based conflict resolution techniques carry a price, which includes our willingness to listen to people and ideas we do not like or accept and share power and control over outcomes with people who are very different from ourselves.

Ultimately, transcending conflict means giving up unequal, inequitable, and autocratic power- and rights-based practices, and seeking instead to address the underlying, chronic reasons people adopted power- and rights-based approaches in the first place. This means surrendering our ability to use force to take from others what does not belong to us or coerce them into giving us what they are otherwise unwilling to give.

These transcendent, interest-based solutions teach us to access the power of our powerlessness, recognize that we are all members of the same human family and open our hearts to each other in ways that lead to deeper levels of truth and reconciliation, intimacy and community, peace and justice, love and happiness, democracy and dialogue. Indeed, they encourage us to recognize that each of us, whether as nations, organizations, families or individuals, can do so in every conflict. It may then be possible for us to see that it is all quite simple, as Cornel West realized, and that “… justice is what love looks like in public.”

Conflict Transformation + Social Justice = Transformative Justice

Conflict transformation looks to not simply "resolve" conflict, but to change the underlying causes of a conflict. When this interest-based approach is applied to social change efforts, social justice takes on the form of transformative justice. Transformative Justice doesn't rely upon rights-based institutions, rejects traditional forms of power, and strives to meet the underlying needs and interests of all people involved.

Transformative justice responses and interventions...

1) do not rely on the state (e.g. police, prisons, the criminal legal system, I.C.E., foster care system) though some do rely on or incorporate social services like counseling;

2) do not reinforce or perpetuate violence such as oppressive norms or vigilantism; and most importantly;

3) actively cultivate the things we know prevent violence such as healing, accountability, resilience, and safety for all involved.[2]

Transformative justice also challenges traditional concepts of enemies, seeks to build long term growth based on healing and development of new processes that replace unjust systems. Save the Kids says the following as they define transformative justice:

Social justice activists often identify the oppressor as the enemy. While this is understandable, transformative justice actually challenges this perspective: no one is an enemy; instead, everyone needs to be involved in a voluntary, safe, constructive, and critical dialogue about accountability, responsibility, and the initiative to heal. This means that both activists and oppressors, as well as law enforcement, lawyers, judges, prisoners, community members, teachers, students, politicians, spiritual leaders, and others, must come together. It is for this reason that we should be willing to work with a diversity of people in our push for a better world. Transformative justice looks for the good in others while also acknowledging the complex systems within which we all live.

Transformative justice values conflict as an opportunity for growth, progress, and social justice.

Transformative justice expands the social justice model, which challenges and identifies injustices, in order to create organized processes of addressing and ending those injustices.[3]

Next Steps

Reflection Questions to Encourage a Balance between Conflict Resolution and Social Justice

Examine these questions within the context of your own work or a contemporary global issue that relates to your work in social change.

- Does the process recognize the right of all stakeholders to be involved?

- Are marginalized voices included?

- Does the process avoid neutrality in the face of systemic oppression and power imbalances?

- What actions can be taken to balance power?

- Does the process consider and address the deep underlying needs of those involved?

- Does the process consider long term systemic change? Or does it seek quick peace or quick justice?

- When is the right time to use power as a strategy?

Tools and Tips

Guiding Principles for Just and Sustainable Movements

- Chronic conflicts are traced to their systemic and structural sources where they can be prevented and redesigned.

- Do not sacrifice justice for peace. Value peace only in so far as it advances the basic human interests of all parties involved in the conflict.

- All interested parties from all levels of a community or organization, regardless of identity, are included and invited to participate fully in designing and implementing content, process, and relationships.

- Parties’ participation in any process is voluntary.

- Processes are designed to locate power and agency in voices that have been previously marginalized or excluded from prior processes, so as not to reproduce power imbalances from the larger society in the conflict resolution process. Process facilitators encourage the group to develop awareness of power dynamics.

- Decisions are made by consensus wherever possible and nothing is considered final until everyone is in agreement.

- Diversity and honest differences are viewed as sources of dialogue, leading to better ideas, healthier relationships, and greater unity.

- Everyone’s interests are accepted as legitimate, acknowledged, and satisfied wherever possible and, consistent with others’ interests.

- Stereotypes, prejudices, assumptions of innate superiority, and ideas of intrinsic correctness are considered divisive and seen as one-sided descriptions of more complex, multi-sided, paradoxical realities.

- Openness, authenticity, appreciation, and empathy are regarded as better foundations for communication and decision-making than secrecy, rhetoric, insult, and demonization.

- Dialogue and open-ended questions are deemed more useful than debate and cross-examination.

- Force, violence, coercion, aggression, humiliation, and domination are rejected, both as methods and as outcomes.

- Processes and relationships are considered at least as important as content, if not more so.

- People are invited into heartfelt, spiritual communications and inner awareness, and encouraged to reach resolution, forgiveness, and reconciliation.

- Victory is regarded as obtainable by everyone, and redirected toward collaborating to solve common problems, so no one feels defeated.

- Interest-based conflict resolution approaches should not, as a rule, exclude or supplant rights-based advocacy and protest. Each method can be evaluated in light of the strategic context, or used in tandem or cooperation.

Challenging Edges

Exploring the Tension between Conflict Resolution and Social Justice

The following questions arise from deep and real concerns about the tensions between Social Justice and Conflict Resolution. The answers indicate how some in the conflict resolution field have addressed these concerns, but they continue to be important open questions.

What is the best way to respond to oppression/extreme power differentials? (When do you advocate and protest through a rights-based system? When do you choose an interest-based, collaborative approach?)

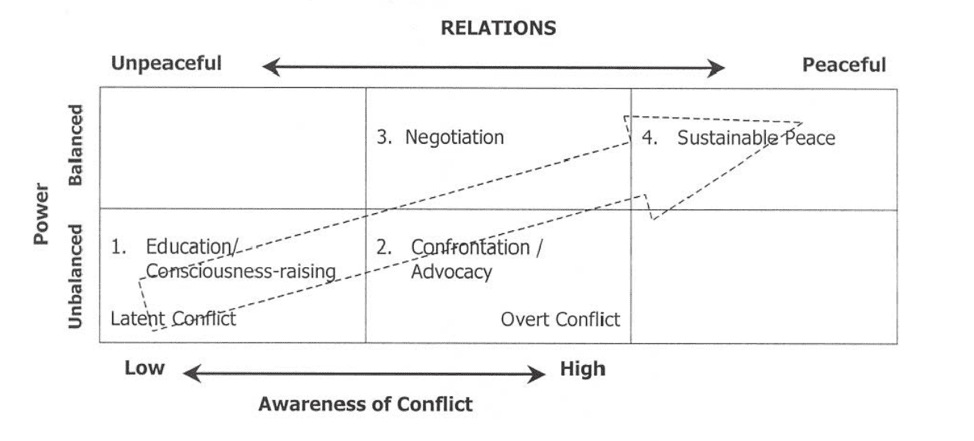

According to John Paul Lederach (inspired by Adam Curle) in his book Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures, the phases of conflict transformation are,

- Education/Consciousness Raising

- Confrontation/Advocacy

- Negotiation

- Sustainable Peace

Negotiation and efforts for collaboration can't be used until there is a balance of power. When power imbalances and systemic oppression are not addressed in a process, it can create settlements that favor the powerful and support the imbalance of power. This is well explained in an article by Just Associates, "Dynamics Of Power, Inclusion And Exclusion"[4] which also provides this graphic:

When and how can you negotiate with the opposition (the enemy)?

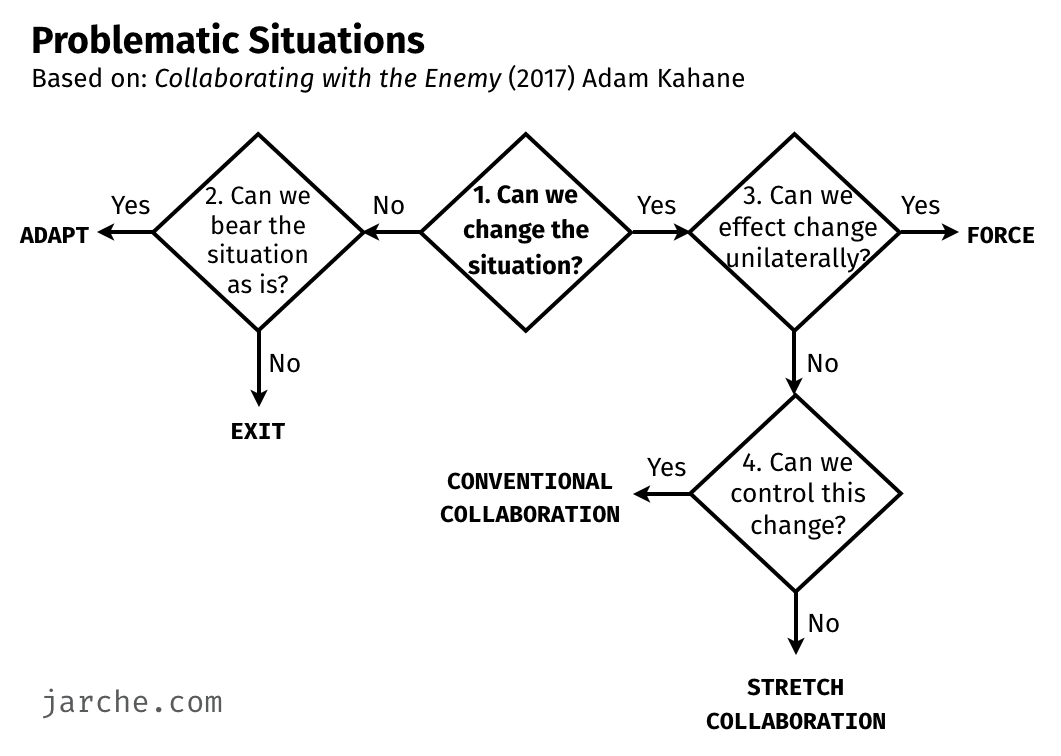

In his book Collaborating with the Enemy: How to Work with People You Don't Agree with or Like or Trust, author Adam Kehane offers a process called "stretch collaboration" for use in situations where there is enmity between the people who need to collaborate.

"Stretch collaboration" can be used when a problematic situation is changeable, can't be changed unilaterally and making the change is risky.[5] Here is a summary of the process:

- “...’embrace conflict and connection.’ ...true collaboration involves both engaging with others (‘love’) and advocating for one’s own interests (‘power’).

- “...’experiment a way forward.’ To do this, participants must ‘stretch away from insisting on clear agreements about the problem, the solution, and the plan, and move toward experimenting systematically with different perspectives and possibilities.’ …’In stretch collaboration, we co-create our way forward.’

- “...’step into the game,’...’we must stretch away from trying to change what other people are doing, and move toward entering fully into the action, willing to change ourselves.’ Systems can only change if every participant is willing to change his or her own behavior.”

This decision tree (from Collaborating with the Enemy) maps out the possible strategies for organizations to use in the face of problematic situations:

Is violence ever justified in social justice struggles? Is it ever strategic? Is nonviolent resistance a moral absolute or a strategic choice? Or both?

Nonviolence is not the same as conflict resolution. Nonviolence is a strategy for engaging in conflict against an oppressive system. While a thorough treatment of this subject is outside the scope of this module, recent research suggests that nonviolence is 10 times more effective than violence in creating sustainable change in society.[6]

In choosing an interest-based, rather than a rights or power-based approach, do we risk duplicating or reifying power imbalances and injustice that exist in the larger society?

As Meg-John Barker asks in “Privilege & Oppression, Conflict & Compassion,” is conflict resolution our “cover story?” “Are we drawn to resolution in order to avoid acknowledging (and to maintain) our own (for example, white) privilege?”

Furthermore, when we give all voices space to be heard, do we risk inadvertently legitimizing or promoting views that are against our principles? Do we risk subjecting some individuals to hate speech, microaggressions or other forms of discrimination or harm?

It is important that process facilitators reflect on these questions as they develop strategy and design conflict resolution processes. In contexts of oppression and power imbalance, it is essential that process facilitators develop internal awareness their own identity and of where they sit in relation to the conflict and to the balance of power among parties. Click here for “Guiding Principles” for conflict transformation processes that support just and sustainable resolution or transformation.

Resources

Books & Articles

Barker, M. & Heckert, J. (2011). “Privilege & Oppression, Conflict & Compassion.” Originally published by The Sociological Imagination.

Cloke, Ken. Politics, Dialogue and the Evolution of Democracy. GoodMedia Press, 2018.

[1]Cloke, Ken. Conflict Revolution. (Second Edition) Goodmedia Publications, 2015.

Cloke, Ken "Conflict and Movements for Social Change: The Politics of Mediation and the Mediation of Politics."

Haight, Jonathan. Righteous Mind. Vintage, Reprint edition, 2013.

Kahane, Adam. Collaborating with the Enemy: How to Work with People You Don't Agree with or Like or Trust. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2015.

Lederach, John Paul. Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures, Syracuse University Press, 1996.

[2]Mia Mingus, "Transformative Justice: A Brief Description" TransformHarm.org

[3]Save the Kids "Defining Transformative Justice" (Anthony Nocella)

[4]Just Associates, "Dynamics Of Power, Inclusion And Exclusion" (Excerpt from: Drawn from VeneKlasen, Lisa with Valerie Miller. A New Weave of Power, People & Politics: The Action Guide for Advocacy and Citizen Participation. Oklahoma City: World Neighbors, 2002.)

[5]Heather McLeod Grant, "Stretching Toward Solutions," Stanford Social Innovation Review, Fall 2017.

[6]"Nonviolent resistance proves potent weapon" Harvard Gazette, Feb 2019, review of Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict by Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan.